- Translated from: Neither α nor Pre-multiplied (Chinese Version)

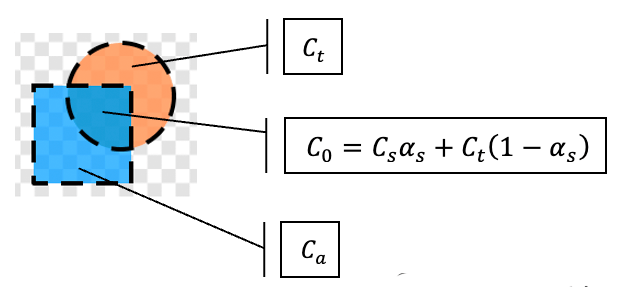

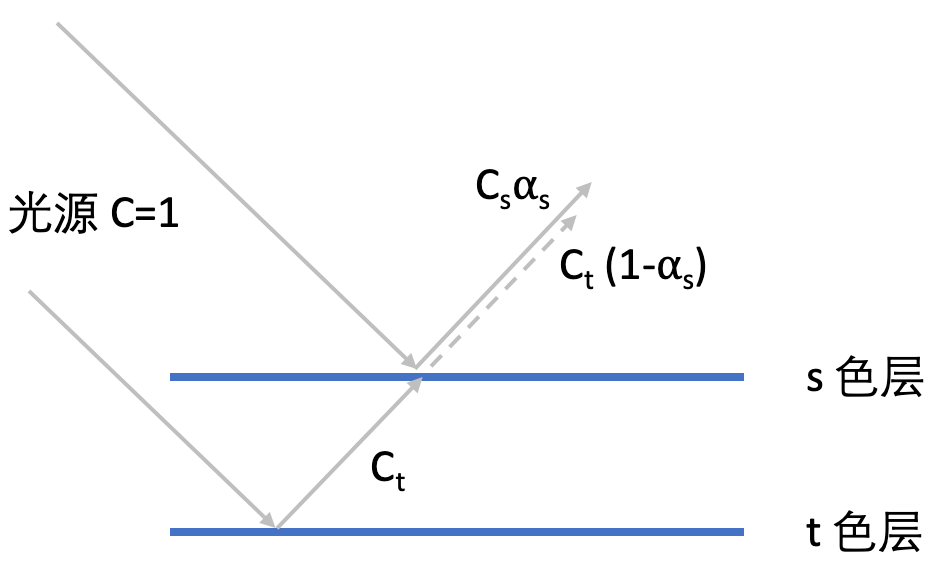

In the domain of image processing and computer graphics, α-blending is a frequently mentioned concept. The following diagram illustrates the α-blending process of an s layer and a t layer. It is a customary way to describe the setup as the s layer being blended on top of the t layer.

Like any mathematical methods, it can be seen as an arbitrary definition, with which no inherent meaning is bound but only what dictated by an application context. However, we also hope that it represents some physical interpretation much more naturally than it would do for others, thus justifying the widespread reference to it.

In the definition above, the value range of αs is [0, 1]. In the attempt to assign a reasonable physical interpretation, let’s first look at the upper bound of the value range where αs = 1, which represents the s layer being completely opaque. At this time, α-blending can be seen as reduced to the ‘full occlusion’ phenomenon in the real world. Now decrease αs to a less-than-one value. The t layer then contributes Ct(1-αs) to the blending result. At this point, we can say that the s layer has a ‘transmittance’ of (1-αs), and its own color is reduced to a portion, that is, αs of what its color was when αs = 1. Since here we mentioned the ‘color’ of a layer, let’s explain the physical meaning of the color of an object.

Mean of Colors

First, we suggest that readers’d better be familiar with the concept of radiometry (but it’s okay if you’re not, many things can be understood intuitively in a non-rigorous manner). In the basic concepts of radiometry, color is an attribute of light, the energy spectrum, rather than of objects. When we talk about the “color of an object”, there are two scenarios: one is for self-luminous objects, and the other refers to the reflectance of the object’s surface. The latter’s true displayed color is the entire subject of the physically-based rendering. Here, we simply assume that the object has no reflectance character but a diffuse reflectance coefficient [1], and its displayed color under parallel white light [2] is of a similar formula to that of a self-luminous object.

Now, let’s consider the meaning of α under this setting. Intuitively, when light enters one side of a layer, a portion (1-α) of it passes through and emerges from the other side [3]. We set up such a scenario: there is a completely opaque layer (α = 1) with a diffuse reflectance coefficient of C [4]. By some means, its α is decreased to a positive number less than 1, resulting in its transmittance becoming (1-α). The question then is whether there exists a “naturally reasonable” physical model based on a single α parameter that makes its diffuse reflectance coefficient to change to Cα simultaneously. If such a naturally reasonable model exists, the definition of α-blending would become more meaningful.

Dilemma to a Universal α

To following the mission mentioned at the end of the last paragraph, we are trying to design such a model. First, we assume that the semi-transparent layer is optically ‘isotropic’, meaning that the interaction with light occurring on its two surfaces are following identical rules. Therefore, the fact that (1-αs) portion of light that passes through the s layer implies that the amount of light the layer reflects is decreased to αs portion of what its opaque counterpart would reflect, equivalent to the descrease of the diffuse reflectance coefficient to Csαs. Is this analysis sound?

Before answering yes or no to its soundness, let’s review the completely opaque situation where αs = 1. In this case, the reflectance coefficient Cs implies that the layer ‘absorbed’ (1-Cs) portion of the incident light energy. So, when αs is reduced in some way, the light passing through the layer doesn’t have to come from the reduction of the reflected light. It could also come, in part or in whole, from avoiding ‘absorption’ of light. Therefore, in an intuitive physical model, using Csαs to represent a new diffuse reflectance coefficient of the semi-transparent color layer is not necessarily the most natural or straightforward choice of physical meaning. The diffuse reflectance coefficient of a layer and its transmittance don’t have a relationship corresponding to a universal αs. It can be rightly argued that the diffuse reflectance coefficient of a semi-transparent layer should be a parameter independent of Cs and αs.

Pre-multiplied α-Blending

Even after having failed to find a natural and straightforward choice of physical interpretation for α-blending, can we take a step back and say it’s not a big issue? Because the simplest other choice is to treat it purely as an ‘artistic effect’. Is it? Let’s examine the situation below.

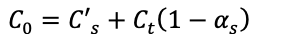

For example, in a software that implements two layers as its internal data representation, layers s and t each has its C and α properties (referred to as channels). At one moment, on the screen, we want to reduce their on-screen size to 1/3 of the original and overlap them using α-blending. From the mathematical definition of α-blending, we can see that there are two options to correctly render this effect. One way is to first blend at the original size and then resize the result. Not only is this method inefficient, but the more severe issue is that it cannot handle more complex cases where the two layers have different offsets, rotations, and scaling factors. Another approach is to resample the two layers according to screen coordinates first and then perform the ‘correspondingly remaining part of’ α-blending. However, what needs to be noted here is that, for the result to be correct, when resampling the s layer, one can’t simply process Cs and αs separately. Instead, the Csαs has to be treated as a collectively virtual channel in the resample process. This requirement leads to implementation difficulties. In today’s computer architecture, a common implementation for layers in graphics hardware is as textures, and the hardware implementation for texture resampling is performed for individual channels independently. To adapt to this hardware constraint, graphics software has developed a concept where the color channel of the texture stores the product of Cα instead of the original C (to make the aforementioned ‘virtual channel’ into actual channel in data representation, which we refer to as C’. The ‘correspondingly remaining part of’ α-blending then becomes:

This method is called pre-multiplied α-blending. The corresponding texture storage method is called pre-multiplied α channels.

From the above two sections, we see that the demand to a naturally fit physical model and hardware implementation constraints have significantly diminished the value of our original idea to give the product Csαs some justified meaning. Instead, the new form of the term, C’s, seems a more attractive notation. But some people may disagree with throwing Csαs out of the window, yet. So let’s say for now we have got the form C’s yet preserve two interpretations for it, either as an intrinsic physical property or still as the product of the Cs and αs factors. In the latter interpretation, C’s must be less than Csαs, and its upper bound must not exceed 1.

More Physically-based Analysis

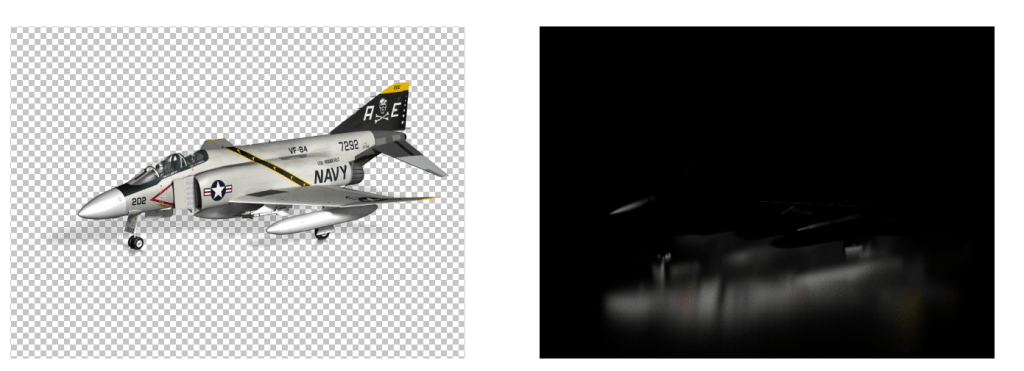

Our previous examples limited to thinking of layers like semi-transparent thin films or pure artistic effects. In this chapter, we move beyond that to consider how layers are used to simulate more realistic physical scenarios. In the example below are two layers, the bottom one representing a real scene captured by camera, while the top one the result of 3D rendering. Their blending result encompasses four different physical scenarios.

简单遮盖:full occlusion

阴影:shadow

反射:specular reflection

These four scenarios all conform to the general formula below, only requiring different parameters. And this formula happens to be the same as the pre-multiplied α-blending form mentioned above.

Full occlusion doesn’t require much discussion. Semi-transparent occlusion is very similar to the thin film color layer discussed earlier. It reduces the background color by a factor of αs. However, the color C’s of the foreground s layer is no longer merely a diffuse reflection parameter, but a full reflectance calculation including the specular reflection [5]. The color of the light reflected by a real semi-transparent object can be any positive number (values exceeding the screen/file-format dynamic range will eventually be clipped). Shadows also result in a decrease in the background layer color, with the degree of reduction being αs. In the shadowed area, the foreground layer color C’s is 0. Specular reflection results in an addition to the blending result. There is no reduction in the background color in this case, hence αs = 0. The foreground layer C’s is the rendering result of the reflection. It’s possible for the same area to have semi-transparent occlusions, shadows, and reflection effects simultaneously.

In these four cases, although the formula of blending is of the same form as that of a pre-multiplied α-blending, their meanings are quite different. This is partially confirmed by the following aspects:

- In such a blending process, the value range of C’s is an arbitrary positive number, whereas in pre-multiplied α-blending, the value of C’s is restricted to [0, Csαs], with an upper bound of 1 [6].

- In such a blending process, C’s does not carry the meaning of a product of Csαs.

Should Not Use Pre-multiplied α but Have to

To recap the above discussion, the commonly used layer blending, especially one that simulates real-world effects, follows formula:

Although the form of this formula is accidentally the same as that of pre-multiplied α-blending, it is interpreted in a much different way.

How about give this blending a name, say r-blending? Hence after, when applying it, we no longer mention α-blending at all. Yes, this is the first proposal I want to put forward in this blog post. But the issue with this proposal of avoiding mentioning α is that, after all, α still exists in the formula. Perhaps some still want to categorize it as a variant of α-blending (but I’m not among them). To this, I want to say, at the very least, do not associate this form with the term pre-multiplied.

However, even so, there’s an inescapable ecosystem issue. One of the tools commonly used for layer blending is Photoshop (or tools that faithfully follow the Photoshop paradigm). Photoshop supports only α-blending. It never knows the r-blending we discussed, and its internal data representation doesn’t support pre-multiplied α channels, either. The only place Photoshop handles pre-multiplied α is during file import, where it will convert color channels in all files labeled as pre-multiplied α to an un-multiplied internal representation for any further edit or process.

Therefore, if a tool wants to produce images that could be used in Photoshop as layers for r-blending, it needs to take some counterintuitive measures. For example, for the aforementioned rendering result, even though it has nothing to do with pre-multiplied channels, to trick Photoshop into doing what we want, when storing this rendering result into a file, it needs to be labeled as pre-multiplied-α channels. This way, when Photoshop opens the file, it will divide each color channel by the α-channel [7]. And then multiply it back if there is a blending happens. These back-and-forth operations cancel each other to produce a result that is roughly correct [8]. Well, most of time but not always.

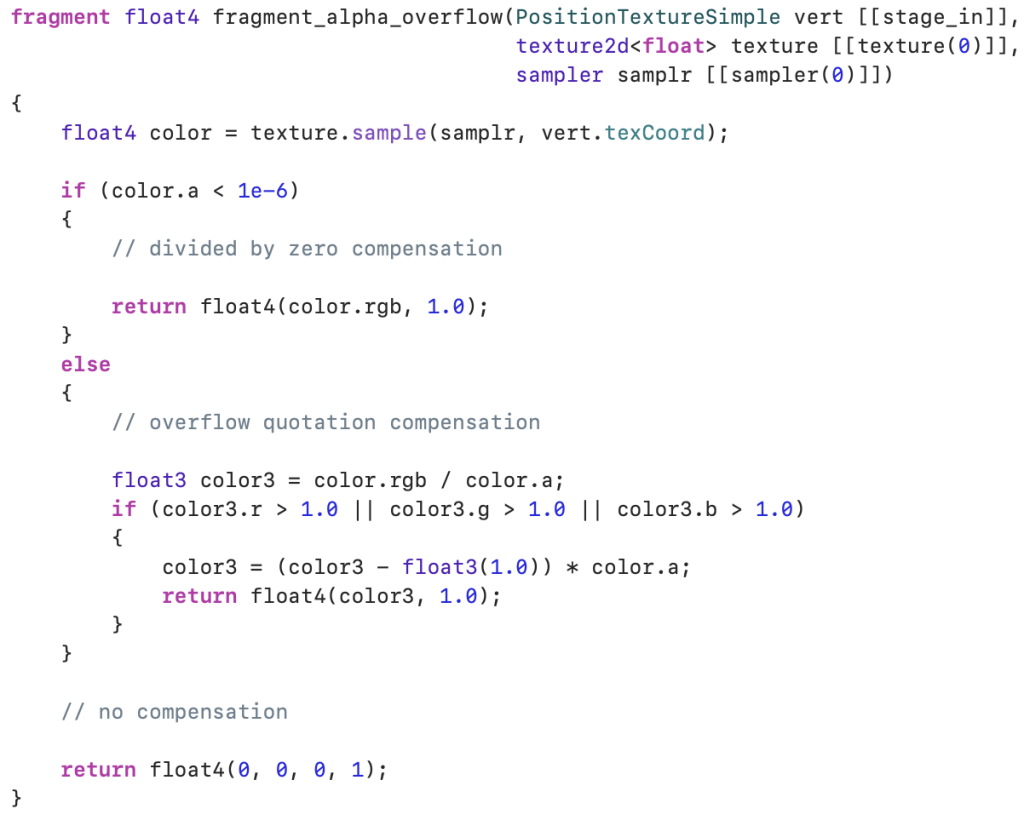

As mentioned above, the results of 3D rendering sometimes fall into the following two scenarios, where the above unmultiplication approach does not work well:

- α-channel is zero. This is typical in the case of specular reflection. In such situations, the data import of Photoshop would lead to a divided-by-zero error. Therefore, in such cases, Photoshop simply sets the color channel to zero.

- The value of a color channel is greater than α, which violates the previously mentioned upper bound assumption of pre-multiplied-α data. In this case, the quotient of the two is greater than one, Photoshop trims the value to 1, and multiplies it by α during blending, resulting in a final value that is lower than the correct value.

There’s no way to produce a layer that allows Photoshop to perform r-blending completely. Therefore, a workaround is needed. One such is to generate a third layer and use Photoshop’s Add blending mode (Linear Dodge) to recover the lost/trimmed portion of color channels.

The left image above shows the loss of data after the rendering result is imported into Photoshop as pre-multiplied-α data converted to un-multiplied. The right image shows the information lost in the unmultiplication, which could be used as Add-blending layer. For reference, here’s the shader used to generate the Add-blending layer:

Conclusion

The definition of α-blending is very simple, yet very often discussions involving it in actual cases brings various confusions. This blog starts with the original definition. Its goal is to explore the origins of these confusions.

From the initial discussion, we can see that the original definition of α-blending does not naturally conform to a simple physical model. One the other hand, the commonly used algorithms of current graphics hardware is not compatible with α-blending, thus proposing such a makeshift solution as pre-multiplied-α. This raises a question: how can such a flawed definition become widely adopted? The answer is that what has been widely adopted is not actually α-blending; In may cases, what is called α-blending is just a misleading term used by various software, with Photoshop being a representative, to mistakenly refer to a process we called r-blending in this blog.

Many physically meaningful scenarios can be modeled as what we named the r-blending process. Since the formula for r-blending coincidentally matches the form of pre-multiplied-α blending, its application often calls for existing implementation in hardware and system libraries named after pre-multiplied-α. However, referring to the concepts of α-blending and pre-multiplication in such scenarios has no benefits, only adding to the confusion.

On the user-oriented front, widely used tools, like Photoshop, stubbornly stick to the α-blending concept. The power of habit is so strong that α-blending and pre-multiplication continue to create confusion and unnecessary work.

Foot Notes:

- Such a surface is usually referred to as an ideal Lambertian surface.

- Due to the simplified situation where only diffuse reflection considered, the direction of the light source is not important.

- In this setting, α is not a differential attribute but an overall volumetric property. For a “layer” similar to a thin film, this is an acceptable simplification.

- C is a function of the spectrum. In typical software implementation, C consists of three parameters (red, green, blue).

- Layers in this section are no longer like the thin films under a light source. Rather they are more considered like the film in a camera, capturing light rays from a scene (or the virtual object supposed to be in a scene).

- In systems that claim to support pre-multiplied α-blending, if the layer’s C’s violates this assumption of bound, it can sometimes cause the system to malfunction. This will be discussed in the following section.

- We also call this process unmultiplication in the following discussion.

- Most of Photoshop’s processing is still based on 8-bit, the precision loss from this repeated multiplication and division is not insignificant in some cases.